Land and biodiversity policies/Forestry sector: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(added references to afforestation policy section) |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{PolicyResponsePartTemplate | {{PolicyResponsePartTemplate | ||

|PageLabel= | |PageLabel=Forestry sector | ||

|Sequence=4 | |Sequence=4 | ||

| | |Reference=FAO, 2013a; IEA, 2012; Putz et al., 2012; | ||

{{DisplayFigureLeftOptimalTemplate|Flowchart | }} | ||

<div class="page_standard"> | |||

<h2>Interventions targeting the forestry sector</h2> | |||

{{DisplayFigureLeftOptimalTemplate|Flowchart Land and biodiversity policies (C)}} | |||

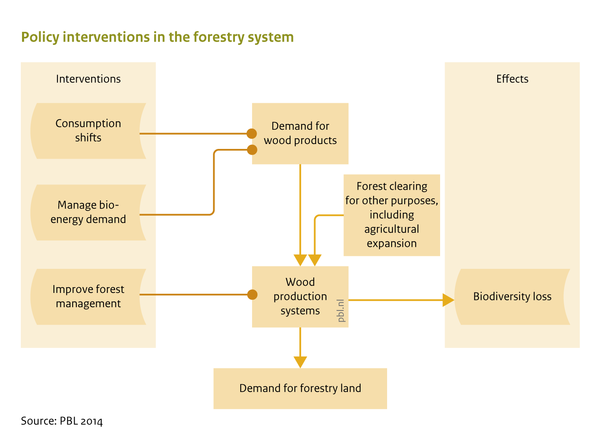

Reducing the rate of agricultural expansion can lead to fewer wood products from forest clearance / deforestation, and thus to an increase in the forest area to meet the wood demand ([[PBL, 2010]]); see also Component [[Forest management]]. Options for alternative forest management have been evaluated in [[Rethinking Biodiversity Strategies (2010) project|Rethinking Global Biodiversity Strategies]] ([[PBL, 2010]]). | |||

</div> | |||

'''Afforestation for climate change mitigation''' | |||

Planting forest on former agricultural land results in the storage of carbon in plant biomass. These negative emissions can be crucial to achieve stringent climate targets. In IMAGE, forest can be expanded by reducing agricultural land. Forest can be grown through natural regeneration or through active planting and management of trees (similar to wood plantations) to enhance forest growth ([[Braakhekke et al., 2019]]). The extent of afforestation can be applied cost-optimally by making afforestation dependent on the carbon price as determined in the [[climate policy]] model ([[Doelman et al., 2019]]). In this way, afforestation is compared to other climate change mitigation options in the energy system and in agriculture. Alternatively, afforestation can be prescribed based on government policies or international ambitions. | |||

{{#default_form:PolicyResponsePartForm}} | |||

{{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | |||

|Header=Shifts in consumption | |||

|Description=Interventions targeting shifts in consumption of forest products have a direct effect on timber demand and, thus also affect the need for forestry areas in production (PBL, 2010). The increase in demand could concern industrial roundwood or paper, but also wood as traditional bioenergy. As a first-order effect, an intervention to change demand for industrial products reduces all upstream effects of production proportionally. Data on wood for traditional biomass are not available, and estimates vary greatly partly due to whether the focus is on use or production. With estimates ranging from 1300 Mt/y ([[FAO, 2013a]]) to 2400 Mt/y ([[IEA, 2012]]), a considerable proportion of the total wood use can be attributed to fuelwood. A decrease in wood use for traditional biomass has fewer direct impacts on the IMAGE biodiversity results than decreases in other uses, because only part of the production is harvested in industrial forestry activities (see Component [[Forest management]]). Large quantities of fuelwood are collected or produced in areas smaller than included in the level of detail of the IMAGE framework, such as orchards and road-sides. This implies that interventions related to this kind of use do not completely show up in biodiversity impacts. | |||

|PISet=Increase access to water; | |||

}} | }} | ||

{{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | {{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | ||

|Header= | |Header=Bio-energy demand | ||

|Description= | |Description=Bioenergy demand will affect demand for forestry products for the energy sector, with effects similar to those expected under the shifts in consumption. The impact on biodiversity will depend on the sustainability criteria, management practices, and regions in which timber is harvested. | ||

|PISet= | |PISet=Implementation of sustainability criteria in bio-energy production; | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | {{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | ||

|Header= | |Header=Improve forest management | ||

|Description= | |Description=Improving forest management will affect the area required to meet timber demand and the impact of timber harvest on biodiversity loss. A system of Reduced Impact Logging ({{abbrTemplate|RIL}}), which relates to improvements that can be implemented in selective logging management, could reduce harvest damage, stimulate regrowth and maintain biodiversity ([[Putz et al., 2012]]). In addition, dedicated plantations could be established and would reduce the area of natural forest needed for timber harvest, since wood production is higher in plantation areas. However, biodiversity values of those areas are relatively low. | ||

|PISet= | |PISet=More sustainable forest management; Expanding Reduced Impact Logging; Increase forest plantations | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | {{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{ContentPartsTemplate}} | {{ContentPartsTemplate}} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:34, 16 June 2021

Parts of Land and biodiversity policies/Forestry sector

| Relevant overviews |

| References |

Interventions targeting the forestry sector

Reducing the rate of agricultural expansion can lead to fewer wood products from forest clearance / deforestation, and thus to an increase in the forest area to meet the wood demand (PBL, 2010); see also Component Forest management. Options for alternative forest management have been evaluated in Rethinking Global Biodiversity Strategies (PBL, 2010).

Afforestation for climate change mitigation

Planting forest on former agricultural land results in the storage of carbon in plant biomass. These negative emissions can be crucial to achieve stringent climate targets. In IMAGE, forest can be expanded by reducing agricultural land. Forest can be grown through natural regeneration or through active planting and management of trees (similar to wood plantations) to enhance forest growth (Braakhekke et al., 2019). The extent of afforestation can be applied cost-optimally by making afforestation dependent on the carbon price as determined in the climate policy model (Doelman et al., 2019). In this way, afforestation is compared to other climate change mitigation options in the energy system and in agriculture. Alternatively, afforestation can be prescribed based on government policies or international ambitions.

Shifts in consumption

Interventions targeting shifts in consumption of forest products have a direct effect on timber demand and, thus also affect the need for forestry areas in production (PBL, 2010). The increase in demand could concern industrial roundwood or paper, but also wood as traditional bioenergy. As a first-order effect, an intervention to change demand for industrial products reduces all upstream effects of production proportionally. Data on wood for traditional biomass are not available, and estimates vary greatly partly due to whether the focus is on use or production. With estimates ranging from 1300 Mt/y (FAO, 2013a) to 2400 Mt/y (IEA, 2012), a considerable proportion of the total wood use can be attributed to fuelwood. A decrease in wood use for traditional biomass has fewer direct impacts on the IMAGE biodiversity results than decreases in other uses, because only part of the production is harvested in industrial forestry activities (see Component Forest management). Large quantities of fuelwood are collected or produced in areas smaller than included in the level of detail of the IMAGE framework, such as orchards and road-sides. This implies that interventions related to this kind of use do not completely show up in biodiversity impacts.

| Policy intervention | Description | Implemented in/affected component |

|---|---|---|

| Increase access to water | Increase access to safe drinking water and improved sanitation by lowering prices and investing in infrastructure |

(*) Implementing component.

Bio-energy demand

Bioenergy demand will affect demand for forestry products for the energy sector, with effects similar to those expected under the shifts in consumption. The impact on biodiversity will depend on the sustainability criteria, management practices, and regions in which timber is harvested.

| Policy intervention | Description | Implemented in/affected component |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation of sustainability criteria in bio-energy production | Sustainability criteria that could become binding for dedicated bio-energy production, such as the restrictive use of water-scarce or degraded areas. |

(*) Implementing component.

Improve forest management

Improving forest management will affect the area required to meet timber demand and the impact of timber harvest on biodiversity loss. A system of Reduced Impact Logging (RIL), which relates to improvements that can be implemented in selective logging management, could reduce harvest damage, stimulate regrowth and maintain biodiversity (Putz et al., 2012). In addition, dedicated plantations could be established and would reduce the area of natural forest needed for timber harvest, since wood production is higher in plantation areas. However, biodiversity values of those areas are relatively low.

| Policy intervention | Description | Implemented in/affected component |

|---|---|---|

| More sustainable forest management | Sustainable forest management aims for maintaining long-term harvest potential and good ecological status of forests (e.g. the nutrient balance and biodiversity). This can be implemented by (i) enlarging the return period when a forest can be harvested again; (ii) only using certain fractions of the harvested biomass and leave the remaining part in the forests. | |

| Expanding Reduced Impact Logging | Increasing the share of produced wood yielded with Reduced Impact Logging (RIL) practices instead of conventional logging practices. | |

| Increase forest plantations | Increase the use of wood from highly productive wood plantations instead of wood from (semi-) natural forests. |

(*) Implementing component.