Land and biodiversity policies/Land-use regulation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Oostenrijr (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | {{PolicyResponsePartTemplate | ||

|PageLabel= | |PageLabel=Land-use regulation | ||

|Sequence= | |Sequence=5 | ||

| | |Reference=UNEP-WCMC, 2008; Overmars et al., 2012; | ||

{{DisplayFigureLeftOptimalTemplate|Flowchart | }}<div class="page_standard"> | ||

<h2>Land-use regulation</h2> | |||

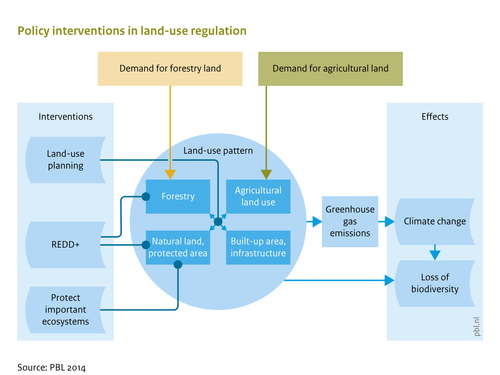

Demand and production technology determine the overall demand for agricultural and forestry land. However, land-use patterns and agricultural areas may also be influenced by regulating the land area available for specific purposes. Land allocation can be restricted in several ways. | |||

{{DisplayFigureLeftOptimalTemplate|Flowchart Land and biodiversity policies (D)}} | |||

</div> | |||

{{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | |||

|Header=Land-use planning | |||

|Description={{DisplayFigureTemplate|Flowchart Land and biodiversity policies (B)}}{{DisplayFigureTemplate|Flowchart Land and biodiversity policies (A)}} | |||

Land-use planning directly affects the land-use pattern, which determines the impact on climate and biodiversity and could enhance the use of ecosystem functions. Measures, such as zoning plans and land registration, designate land areas to certain uses, including protected areas and natural corridors between designated agricultural land areas. The purpose of such natural corridors is to limit the impact on biodiversity of large agricultural areas and to connect individual spots rich in biodiversity. Restricting the land area for agriculture could affect land prices and prices of agricultural commodities thus reduce the relative costs of production factors, such as labour and capital, and other inputs. Such interventions may result in changes to the production system (Figure B) and the demand system (Figure A), and in impacts on biodiversity and climate. | |||

|PISet=Implementation of land use planning; | |||

}} | }} | ||

{{ | {{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | ||

|Header= | |Header=REDD+ schemes or payments for ecosystem services | ||

|Description= | |Description={{DisplayFigureTemplate|Flowchart Land and biodiversity policies (B)}} | ||

|PISet= | Some land uses that also provide ecosystem services could generate additional returns via REDD+ schemes or payments for ecosystem services. Such payments would place a value on ecosystem services that do not have a market value at present and would then compete with other economic activities for the same land area. This intervention would restrict the land available for agriculture or forestry, which would affect land prices and reduce consumption. This could induce adaptations in the production system (Figure B), and consequently alter the impacts on biodiversity and climate at that level. The outcome of introducing payments for ecosystem services are currently most uncertain, as such schemes have not been applied frequently as yet. | ||

|PISet=Avoiding deforestation; REDD policies; | |||

}} | }} | ||

{{ | {{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | ||

|Header= | |Header=Expansion of bioreserves | ||

|Description= | |Description=Expansion of bio-reserves should increase biodiversity values, provided sites are well selected. The climate impact of these protection areas depends on the carbon content of the standing biomass. Most hot spots for biodiversity protection also have high carbon content ([[UNEP-WCMC, 2008]]). Furthermore, the impact of this intervention on agricultural production depends on the productivity level in these areas. Restricting the land area available for agriculture could affect land prices. Consequently, the same impacts as described under land-use planning could be expected. Expansion of bio-reserves has been analysed by PBL ([[PBL, 2010]]; [[PBL, 2012]]), and an evaluation of costs and CO<sub>2</sub> emission reductions via {{abbrTemplate|REDD+}} schemes has been made by Overmars et al. ([[Overmars et al., 2012| 2012]]). | ||

|PISet=Enlarge protected areas; | |||

|PISet= | |||

}} | }} | ||

{{ContentPartsTemplate}} | |||

{{#default_form:PolicyResponsePartForm}} | |||

Latest revision as of 09:51, 20 November 2018

Parts of Land and biodiversity policies/Land-use regulation

| Relevant overviews |

| References |

Land-use regulation

Demand and production technology determine the overall demand for agricultural and forestry land. However, land-use patterns and agricultural areas may also be influenced by regulating the land area available for specific purposes. Land allocation can be restricted in several ways.

Land-use planning

Land-use planning directly affects the land-use pattern, which determines the impact on climate and biodiversity and could enhance the use of ecosystem functions. Measures, such as zoning plans and land registration, designate land areas to certain uses, including protected areas and natural corridors between designated agricultural land areas. The purpose of such natural corridors is to limit the impact on biodiversity of large agricultural areas and to connect individual spots rich in biodiversity. Restricting the land area for agriculture could affect land prices and prices of agricultural commodities thus reduce the relative costs of production factors, such as labour and capital, and other inputs. Such interventions may result in changes to the production system (Figure B) and the demand system (Figure A), and in impacts on biodiversity and climate.

| Policy intervention | Description | Implemented in/affected component |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation of land use planning | Application of zoning laws or cadastres, assigning areas to certain land uses. |

(*) Implementing component.

REDD+ schemes or payments for ecosystem services

Some land uses that also provide ecosystem services could generate additional returns via REDD+ schemes or payments for ecosystem services. Such payments would place a value on ecosystem services that do not have a market value at present and would then compete with other economic activities for the same land area. This intervention would restrict the land available for agriculture or forestry, which would affect land prices and reduce consumption. This could induce adaptations in the production system (Figure B), and consequently alter the impacts on biodiversity and climate at that level. The outcome of introducing payments for ecosystem services are currently most uncertain, as such schemes have not been applied frequently as yet.

| Policy intervention | Description | Implemented in/affected component |

|---|---|---|

| Avoiding deforestation | Here comes description | |

| REDD policies | The objective of REDD policies it to reduce land-use related emissions by protecting existing forests in the world; The implementation of REDD includes also costs of policies. |

(*) Implementing component.

Expansion of bioreserves

Expansion of bio-reserves should increase biodiversity values, provided sites are well selected. The climate impact of these protection areas depends on the carbon content of the standing biomass. Most hot spots for biodiversity protection also have high carbon content (UNEP-WCMC, 2008). Furthermore, the impact of this intervention on agricultural production depends on the productivity level in these areas. Restricting the land area available for agriculture could affect land prices. Consequently, the same impacts as described under land-use planning could be expected. Expansion of bio-reserves has been analysed by PBL (PBL, 2010; PBL, 2012), and an evaluation of costs and CO2 emission reductions via REDD+ schemes has been made by Overmars et al. ( 2012).

| Policy intervention | Description | Implemented in/affected component |

|---|---|---|

| Enlarge protected areas | Increase in areas with protected status, as well the size of the areas as the numer of parks. |

(*) Implementing component.