Forest management: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Dafnomilii (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (62 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ComponentTemplate2 | {{ComponentTemplate2 | ||

|IMAGEComponent= | |Application=Rethinking Biodiversity Strategies (2010) project;Shared Socioeconomic Pathways - SSP (2014) project;EU Seventh Framework Programme - FP7;LUC4C | ||

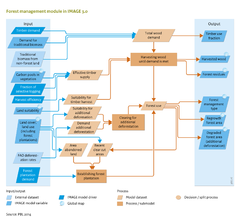

|InputVar= | |IMAGEComponent=Drivers;Land-use allocation;Carbon cycle and natural vegetation;Energy supply and demand | ||

FAO deforestation rates | |KeyReference=Arets et al., 2011 | ||

|OutputVar=Timber use fraction; | |Reference=Carle and Holmgren, 2008;Putz et al., 2012;FAO, 2006b;Alkemade et al., 2009;Hartmann et al., 2010;FAO, 2015;Dagnachew et al., 2018;Dagnachew et al., 2020;Doelman et al., 2019;Doelman et al., 2020b;FAO, 2020 | ||

| | |InputVar=Demand traditional biomass;Land cover, land use - grid;Forest plantation demand;Harvest efficiency;Timber demand;Carbon pools in vegetation - grid;Fraction of selective logging;Agricultural land use suitability - grid | ||

|Parameter=Traditional biomass from non-forest land;FAO deforestation rates | |||

|OutputVar=Timber use fraction;Forest residues;Forest management type - grid;Regrowth forest area - grid;Harvested wood;Degraded forest area | |||

|ComponentCode=FM | |||

|AggregatedComponent=Agriculture and land use | |||

|FrameworkElementType=pressure component | |||

}} | |||

<div class="page_standard"> | |||

The global forest area and wooded land area has been estimated for 2010 at just over 40 and 11 million km<sup>2</sup>, respectively ([[FAO, 2020]]). Forest resources are used for multitude of purposes, including timber, fuel, food, water and other forest-related goods and services. In addition, (semi-) natural forests are home to many highly valued species of interest for nature conservation and biodiversity. | |||

The | The total global forest area is continuing to decline at difference rates in different world regions. Although the rate of global deforestation has decreased in the last decade, deforestation is still occurring on a significant scale in large parts of Latin America, Africa and Southeastern Asia. At the same time, the net forest area is expanding in some regions, such as in Europe and China ([[FAO, 2020]]). Sustainable management of global forest resources may contribute to preserving forests, slowing down or reversing degradation processes, and conserving forest biodiversity and carbon stocks ([[FAO, 2020]]). | ||

Several types of forest management systems | Several types of forest management systems are employed in meeting the worldwide demand for timber, paper, fibreboard, traditional or modern bioenergy and other products. Management practices depend on forest type, conservation policies and regulation, economics, and other, often local, factors. Practices differ with respect to timber volume harvested per area, rotation cycle, and carbon content and state of biodiversity of the forested areas. | ||

Modelling of forests and forest management is an integral part of the IMAGE 3.2 framework, with a simulated forest area in 2010 at about 47 million km<sup>2</sup> , somewhat larger than observed by {{abbrTemplate|FAO}} as this area includes fractions of other wooded land (see Component [[Carbon cycle and natural vegetation]]). To manage these forests, three forest management systems are defined in IMAGE 3.2 in a simplification of the range of management systems implemented worldwide ([[Carle and Holmgren, 2008]]; [[Arets et al., 2011]]). | |||

# The first forest management system is clear cutting or clear felling, in which all trees in an area are cut down followed by natural or ‘assisted’ regrowth, as widely applied in temperate regions. | |||

# The second forest management system is selective logging of (semi)natural forests, in which only trees of the highest economic value are felled, commonly used in tropical forests with a high heterogeneity of tree species. An ecological variant of selective logging is reduced impact logging ({{abbrTemplate|RIL}}) directed to reducing harvest damage, stimulating regrowth and maintaining biodiversity levels ([[Putz et al., 2012]]). | |||

# The third forest management system considered in IMAGE 3.2 is forest plantations, such as hardwood tree plantations in the tropics, and poplar plantations in temperate regions. Selected tree species, either endemic or exotic to the area, are planted and managed intensively, for example through pest control, irrigation and fertiliser use, to maximise production. Forest plantation growth is modelled in LPJmL and was recalibrated in IMAGE 3.2 to empirical data ([[Braakhekke et al., 2019]]) as forest plantations generally have a higher productivity level than natural forests ([[FAO, 2006b]]). By producing more wood products on less land, plantations may contribute to more sustainable forest management by reducing pressure on natural forests ([[Carle and Holmgren, 2008]]; [[Alkemade et al., 2009]]). However, the ecological value of biodiversity in many forest plantations is relatively low ([[Hartmann et al., 2010]]). | |||

{{InputOutputParameterTemplate}} | |||

</div> | |||

Latest revision as of 18:14, 22 November 2021

Parts of Forest management

| Component is implemented in: |

| Components: |

| Related IMAGE components |

| Projects/Applications |

| Key publications |

| References |

Key policy issues

- How can management influence forest capacity to meet future demand for wood and other ecosystem services?

- What are the implications of forest management for pristine and managed forest areas, and on biomass and carbon stocks and fluxes of relevance for climate policy?

- What are the prospects for more sustainable forest management and the role of production in dedicated forest plantations?

Introduction

The global forest area and wooded land area has been estimated for 2010 at just over 40 and 11 million km2, respectively (FAO, 2020). Forest resources are used for multitude of purposes, including timber, fuel, food, water and other forest-related goods and services. In addition, (semi-) natural forests are home to many highly valued species of interest for nature conservation and biodiversity.

The total global forest area is continuing to decline at difference rates in different world regions. Although the rate of global deforestation has decreased in the last decade, deforestation is still occurring on a significant scale in large parts of Latin America, Africa and Southeastern Asia. At the same time, the net forest area is expanding in some regions, such as in Europe and China (FAO, 2020). Sustainable management of global forest resources may contribute to preserving forests, slowing down or reversing degradation processes, and conserving forest biodiversity and carbon stocks (FAO, 2020).

Several types of forest management systems are employed in meeting the worldwide demand for timber, paper, fibreboard, traditional or modern bioenergy and other products. Management practices depend on forest type, conservation policies and regulation, economics, and other, often local, factors. Practices differ with respect to timber volume harvested per area, rotation cycle, and carbon content and state of biodiversity of the forested areas.

Modelling of forests and forest management is an integral part of the IMAGE 3.2 framework, with a simulated forest area in 2010 at about 47 million km2 , somewhat larger than observed by FAO as this area includes fractions of other wooded land (see Component Carbon cycle and natural vegetation). To manage these forests, three forest management systems are defined in IMAGE 3.2 in a simplification of the range of management systems implemented worldwide (Carle and Holmgren, 2008; Arets et al., 2011).

- The first forest management system is clear cutting or clear felling, in which all trees in an area are cut down followed by natural or ‘assisted’ regrowth, as widely applied in temperate regions.

- The second forest management system is selective logging of (semi)natural forests, in which only trees of the highest economic value are felled, commonly used in tropical forests with a high heterogeneity of tree species. An ecological variant of selective logging is reduced impact logging (RIL) directed to reducing harvest damage, stimulating regrowth and maintaining biodiversity levels (Putz et al., 2012).

- The third forest management system considered in IMAGE 3.2 is forest plantations, such as hardwood tree plantations in the tropics, and poplar plantations in temperate regions. Selected tree species, either endemic or exotic to the area, are planted and managed intensively, for example through pest control, irrigation and fertiliser use, to maximise production. Forest plantation growth is modelled in LPJmL and was recalibrated in IMAGE 3.2 to empirical data (Braakhekke et al., 2019) as forest plantations generally have a higher productivity level than natural forests (FAO, 2006b). By producing more wood products on less land, plantations may contribute to more sustainable forest management by reducing pressure on natural forests (Carle and Holmgren, 2008; Alkemade et al., 2009). However, the ecological value of biodiversity in many forest plantations is relatively low (Hartmann et al., 2010).

Input/Output Table

Input Forest management component

| IMAGE model drivers and variables | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Fraction of selective logging | The fraction of forest harvested in a grid, in clear cutting, selective cutting, wood plantations and additional deforestation. Fraction of selective cut determines the fraction of timber harvested by selective cutting of trees in semi-natural and natural forest. | Drivers |

| Forest plantation demand | Demand for forest plantation area. | Drivers |

| Harvest efficiency | Fraction of harvested wood used as product, the remainder being left as residues. Specified per biomass pool and forestry management type. | Drivers |

| Timber demand | Demand for roundwood and pulpwood per region. | Drivers |

| Agricultural land use suitability - grid | Suitability of land in a grid cell for agriculture and forestry, as a function of accessibility, population density, slope and potential crop yields. | |

| Land cover, land use - grid | Multi-dimensional map describing all aspects of land cover and land use per grid cell, such as type of natural vegetation, crop and grass fraction, crop management, fertiliser and manure input, livestock density. | Land cover and land use |

| Carbon pools in vegetation - grid | Carbon pools in leaves, stems, branches and roots). | Carbon cycle and natural vegetation |

| Demand traditional biomass | Regional demand for traditional bioenergy. | Energy demand |

| External datasets | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| FAO deforestation rates | Historical deforestation rates according to FAO. | FAO |

| Traditional biomass from non-forest land | Fraction of traditional fuelwood from non-forestry sources, such as orchard, assumed to be 50% (low-income countries) and 68% (middle-income countries). | FAO |

Output Forest management component

| IMAGE model variables | Description | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Harvested wood | Wood harvested and removed. | |

| Degraded forest area | Permanently deforested areas for reasons other than expansion of agricultural land (calibrated to FAO deforestation statistics). | |

| Timber use fraction | Fractions of harvested timber entering the fast-decaying timber pool, the slow-decaying timber pool, or burnt as traditional biofuels. | |

| Forest management type - grid | Forest management type: clear cut, selective logging, forest plantation or additional deforestation. | |

| Regrowth forest area - grid | Areas of re-growing forests after agricultural abandonment or timber harvest. | |

| Forest residues | Harvest losses (from damaged trees and unusable tree parts) or harvest residues that are left in the forest by purpose because of environmental concerns. These losses/residues remains in the forest after harvest, in in principle enter the soil pools. But they could also be used for other/energy purposes. | Final output |