Land and biodiversity policies/Agricultural production system: Difference between revisions

m (Copied from Land and biodiversity policies3/Targeting agricultural demand) |

No edit summary |

||

| (22 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | {{PolicyResponsePartTemplate | ||

|PageLabel= | |PageLabel=Agricultural production system | ||

|Sequence= | |Sequence=3 | ||

}} | }} | ||

<div class="page_standard"> | |||

<h2>Interventions targeting the agricultural production system</h2> | |||

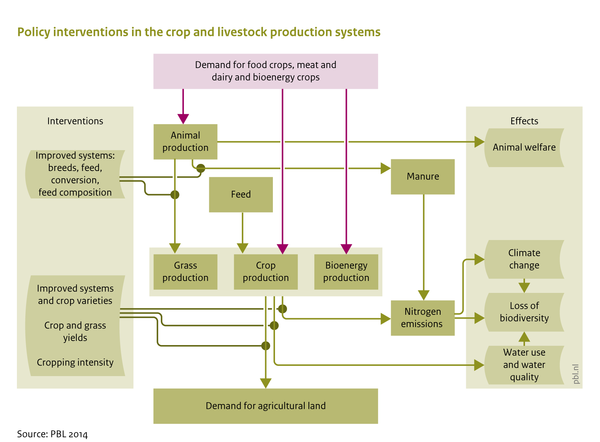

The agricultural production system concerns how animals are raised and crops are cultivated. The characteristics of a particular system, for example what inputs are required to produce one unit of product, define the environmental impacts. Various interventions may increase the efficiency of production systems, and thus lead to reductions in inputs or in environmental impacts. | |||

|PISet= | |||

Results of an efficiency increase in livestock management are presented in the PBL report The Protein Puzzle ([[PBL, 2011]]; [[Stehfest et al., 2013]]). Alternative cropping practices are summarised in Roads from Rio+20 ([[PBL, 2012]]). (see also [[The Protein Puzzle (2011) project]] and [[Roads from Rio+20 (2012) project]]. | |||

{{DisplayFigureLeftOptimalTemplate|Flowchart Land and biodiversity policies (B)}} | |||

</div> | |||

'''Carbon tax in agricultural production''' | |||

Agricultural production produces greenhouse-gas emissions: Fertilization of crops and manure from livestock produce N<sub>2</sub>O emissions, and enteric fermentation from ruminants and production of rice in paddy fields results in CH<sub>4</sub> emissions. By placing a carbon tax on these emissions, similar to policy implemented in the [[Climate policy]] model, these emissions can be reduced in a cost-optimal way. This is implemented in the [[Agricultural economy]] model and results in substitution of consumption towards less emission-intensive products, additional intensification of agricultural production, and in reduced consumption leading to effects on food security. This policy is implemented in a model intercomparison study with IMAGE, GLOBIOM, CAPRI and MAGNET ([[Frank et al., 2018]]). | |||

{{#default_form:PolicyResponsePartForm}} | |||

{{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | |||

|Header=Improve livestock systems | |||

|Description=Interventions to improve livestock systems could include use of breeds that have higher feed conversion rates, require another ratio of feed composites, or produce less manure. Changes in feed conversion or feed composition, for example the ratio of grazing to feed crop feeding, have an impact on demand for grazing and cropland. Thus, changes to these systems will lead to other environmental impacts and other patterns of agricultural land use. For instance, quantity and quality of manure produced affect nitrogen emission levels and thus also nutrient balances and climate change impacts. In addition, biodiversity is affected by nitrogen emissions. Interventions can also be directed to improving animal welfare, but in most cases, higher animal welfare standards require more input per unit of production ([[PBL, 2011]]). Storage and application of manure varies with livestock systems, and affects crop yields and emission levels. A secondary impact of increasing feed efficiencies could be cost reductions, leading to a similar feedback effect as described for changes in demand. | |||

Two interrelated interventions in the cropping system are distinguished: | |||

# improved cropping systems or varieties; | |||

# increasing crop and grass yields or increasing cropping intensity (number of crops per year). | |||

Management in agriculture is an interplay of the cultivar chosen, soil management, fertiliser and other inputs, and the choice and timing of each cultivation step. The first interventions focus on reducing often negative external effects other than land use, and the second intervention targets the use of as small land areas as possible. | |||

|PISet=Change in grazing intensity; Changes in crop and livestock production systems; Changes in feed ration; Improved manure storage; Improvement of feed conversion; Increased livestock productivity; Integrated manure management; Intensification/extensification of livestock systems; Intensification or extensification of livestock systems | |||

}} | }} | ||

{{ | {{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | ||

|Header= | |Header=Improve cropping systems or varieties | ||

|Description= | |Description=Improved cropping systems or varieties could increase the use efficiency of inputs including water and nutrients. Inputs fine-tuned to crop requirements would lead to less nitrogen emissions or less water use per tonne of crop and, would reduce the impacts on biodiversity and climate. While improved management could also lead to higher yields (see below), improved systems could mean a shift in inputs, such as labour, capital, land, fertiliser and water. This may alter the cost price of agricultural products, market prices and consumption. | ||

|PISet=Changes in crop and livestock production systems | |||

}} | |||

|PISet= | {{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | ||

|Header=Crops and grass yields | |||

|Description=Yields can be increased with other varieties, for example, to increase the potential yield, or with improved management (thus, close the yield gap). However, other, more suitable crop varieties often also need different types of management in order to produce higher yields. | |||

|PISet=Changes in crop and livestock production systems; Improved irrigation efficiency; Improved rainwater management; Integrated manure management | |||

}} | |||

{{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | |||

|Header=Cropping intensity | |||

|Description=The cropping intensity can be increased by multiple cropping (more harvests per year) depending on climatic conditions, or by decreasing the area left fallow. Both interventions would decrease the required production area for all crops but could also increase the environmental impacts per hectare of crops. Where lower area requirements decrease biodiversity and climate impacts, the environmental impacts per hectare could increase them again. Thus, to decrease biodiversity loss, yield increases need to go hand in hand with system changes to reduce external impacts. Increased cropping intensity increases the risk of soil degradation without adaptation of cropping rotations or soil management. | |||

|PISet=Changes in crop and livestock production systems | |||

}} | }} | ||

{{ | {{PolicyInterventionSetTemplate | ||

|Header= | |Header=Carbon tax in agricultural production | ||

|Description= | |Description=Agricultural production produces greenhouse-gas emissions: Fertilization of crops and manure from livestock produce N2O emissions, and enteric fermentation from ruminants and production of rice in paddy fields results in CH4 emissions. By placing a carbon tax on these emissions, similar to policy implemented in the [[Climate policy]] model, these emissions can be reduced in a cost-optimal way. This is implemented in the [[Agricultural economy]] model and results in substitution of consumption towards less emission-intensive products, additional intensification of agricultural production, and in reduced consumption leading to effects on food security. This policy is implemented in a model intercomparison study with IMAGE, GLOBIOM, CAPRI and MAGNET ([[Frank et al., 2018]]). | ||

|PISet=Changes in crop and livestock production systems | |||

}} | }} | ||

{{ContentPartsTemplate}} | |||

Latest revision as of 17:17, 20 March 2024

Parts of Land and biodiversity policies/Agricultural production system

| Relevant overviews |

Interventions targeting the agricultural production system

The agricultural production system concerns how animals are raised and crops are cultivated. The characteristics of a particular system, for example what inputs are required to produce one unit of product, define the environmental impacts. Various interventions may increase the efficiency of production systems, and thus lead to reductions in inputs or in environmental impacts.

Results of an efficiency increase in livestock management are presented in the PBL report The Protein Puzzle (PBL, 2011; Stehfest et al., 2013). Alternative cropping practices are summarised in Roads from Rio+20 (PBL, 2012). (see also The Protein Puzzle (2011) project and Roads from Rio+20 (2012) project.

Carbon tax in agricultural production

Agricultural production produces greenhouse-gas emissions: Fertilization of crops and manure from livestock produce N2O emissions, and enteric fermentation from ruminants and production of rice in paddy fields results in CH4 emissions. By placing a carbon tax on these emissions, similar to policy implemented in the Climate policy model, these emissions can be reduced in a cost-optimal way. This is implemented in the Agricultural economy model and results in substitution of consumption towards less emission-intensive products, additional intensification of agricultural production, and in reduced consumption leading to effects on food security. This policy is implemented in a model intercomparison study with IMAGE, GLOBIOM, CAPRI and MAGNET (Frank et al., 2018).

Improve livestock systems

Interventions to improve livestock systems could include use of breeds that have higher feed conversion rates, require another ratio of feed composites, or produce less manure. Changes in feed conversion or feed composition, for example the ratio of grazing to feed crop feeding, have an impact on demand for grazing and cropland. Thus, changes to these systems will lead to other environmental impacts and other patterns of agricultural land use. For instance, quantity and quality of manure produced affect nitrogen emission levels and thus also nutrient balances and climate change impacts. In addition, biodiversity is affected by nitrogen emissions. Interventions can also be directed to improving animal welfare, but in most cases, higher animal welfare standards require more input per unit of production (PBL, 2011). Storage and application of manure varies with livestock systems, and affects crop yields and emission levels. A secondary impact of increasing feed efficiencies could be cost reductions, leading to a similar feedback effect as described for changes in demand.

Two interrelated interventions in the cropping system are distinguished:

- improved cropping systems or varieties;

- increasing crop and grass yields or increasing cropping intensity (number of crops per year).

Management in agriculture is an interplay of the cultivar chosen, soil management, fertiliser and other inputs, and the choice and timing of each cultivation step. The first interventions focus on reducing often negative external effects other than land use, and the second intervention targets the use of as small land areas as possible.

| Policy intervention | Description | Implemented in/affected component |

|---|---|---|

| Change in grazing intensity | Change in grazing intensity, usually more intensive. This would require better management of grasslands, including for example the use of grass-clover mixtures and fertilisers, bringing the length of the grazing season in tune with the period of grass production, and rotations. | |

| Changes in crop and livestock production systems | General changes in crop and livestock production systems, e.g. more efficient production methods to create higher production per unit of input, or other systems like organic farming | |

| Changes in feed ration | Change in the share of grass in the feed rations of cattle, sheep and goats, usually a decrease, meaning grass will be substituted by feed crops and the livestock system will be more intensive. | |

| Improved manure storage | Improved manure storage systems (ST), considering 20% lower NH3 emissions from animal housing and storage systems. |

|

| Improvement of feed conversion | Improvement of feed conversion ratio of small ruminants, such as sheep and goats. This means other breeds will be used that need less grass to produce the same amount of meat. | |

| Increased livestock productivity | A change in production characteristics, such as milk production per animal, carcass weight and off-take rates, which will also have an impact on the feed conversion ratio; in general, this will be lower in more productive animals | |

| Integrated manure management | Better integration of manure in crop production systems. This consists of recycling of manure that under the baseline scenario ends up outside the agricultural system (e.g. manure used as fuel), in crop systems to substitute fertiliser. In addition, there is improved integration of animal manure in crop systems, particularly in industrialised countries. |

|

| Intensification/extensification of livestock systems | A change in the distribution of the production over pastoral and mixed systems; usually to a larger share of the production in mixed systems, which inherently changes the overall feed conversion ratios of ruminants. | |

| Intensification or extensification of livestock systems | A change in the distribution of the production over pastoral and mixed systems; usually to a larger share of the production in mixed systems, which inherently changes the overall feed conversion ratios of ruminants. |

(*) Implementing component.

Improve cropping systems or varieties

Improved cropping systems or varieties could increase the use efficiency of inputs including water and nutrients. Inputs fine-tuned to crop requirements would lead to less nitrogen emissions or less water use per tonne of crop and, would reduce the impacts on biodiversity and climate. While improved management could also lead to higher yields (see below), improved systems could mean a shift in inputs, such as labour, capital, land, fertiliser and water. This may alter the cost price of agricultural products, market prices and consumption.

| Policy intervention | Description | Implemented in/affected component |

|---|---|---|

| Changes in crop and livestock production systems | General changes in crop and livestock production systems, e.g. more efficient production methods to create higher production per unit of input, or other systems like organic farming |

(*) Implementing component.

Crops and grass yields

Yields can be increased with other varieties, for example, to increase the potential yield, or with improved management (thus, close the yield gap). However, other, more suitable crop varieties often also need different types of management in order to produce higher yields.

| Policy intervention | Description | Implemented in/affected component |

|---|---|---|

| Changes in crop and livestock production systems | General changes in crop and livestock production systems, e.g. more efficient production methods to create higher production per unit of input, or other systems like organic farming | |

| Improved irrigation efficiency | Improved irrigation efficiency assumes an increase in the irrigation project efficiency and irrigation conveyance efficiency. |

|

| Improved rainwater management | Improved rainwater management assumes a decrease in the evaporative losses from rainfed agriculture and the creation of small scale reservoirs to harvest rainwater during the wet period and use it during a dryer period. Both measures lead to more efficient use of water and increased yields on rainfed fields. |

|

| Integrated manure management | Better integration of manure in crop production systems. This consists of recycling of manure that under the baseline scenario ends up outside the agricultural system (e.g. manure used as fuel), in crop systems to substitute fertiliser. In addition, there is improved integration of animal manure in crop systems, particularly in industrialised countries. |

|

(*) Implementing component.

Cropping intensity

The cropping intensity can be increased by multiple cropping (more harvests per year) depending on climatic conditions, or by decreasing the area left fallow. Both interventions would decrease the required production area for all crops but could also increase the environmental impacts per hectare of crops. Where lower area requirements decrease biodiversity and climate impacts, the environmental impacts per hectare could increase them again. Thus, to decrease biodiversity loss, yield increases need to go hand in hand with system changes to reduce external impacts. Increased cropping intensity increases the risk of soil degradation without adaptation of cropping rotations or soil management.

| Policy intervention | Description | Implemented in/affected component |

|---|---|---|

| Changes in crop and livestock production systems | General changes in crop and livestock production systems, e.g. more efficient production methods to create higher production per unit of input, or other systems like organic farming |

(*) Implementing component.

Carbon tax in agricultural production

Agricultural production produces greenhouse-gas emissions: Fertilization of crops and manure from livestock produce N2O emissions, and enteric fermentation from ruminants and production of rice in paddy fields results in CH4 emissions. By placing a carbon tax on these emissions, similar to policy implemented in the Climate policy model, these emissions can be reduced in a cost-optimal way. This is implemented in the Agricultural economy model and results in substitution of consumption towards less emission-intensive products, additional intensification of agricultural production, and in reduced consumption leading to effects on food security. This policy is implemented in a model intercomparison study with IMAGE, GLOBIOM, CAPRI and MAGNET (Frank et al., 2018).

| Policy intervention | Description | Implemented in/affected component |

|---|---|---|

| Changes in crop and livestock production systems | General changes in crop and livestock production systems, e.g. more efficient production methods to create higher production per unit of input, or other systems like organic farming |

(*) Implementing component.