Agricultural economy/Policy issues: Difference between revisions

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

m (RinekeOostenrijk moved page Agricultural economy and forestry/Policy issues to Agricultural economy/Policy issues without leaving a redirect) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ComponentPolicyIssueTemplate | {{ComponentPolicyIssueTemplate | ||

|Reference=Banse et al., 2008; Verburg et al., 2009; PBL, 2010; PBL, 2011; Westhoek et al., in preparation; Overmars et al., accepted; | |||

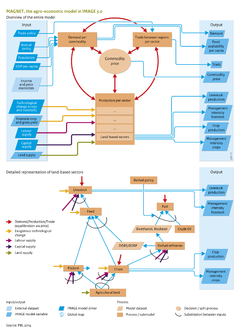

|Description=In a baseline scenario, agricultural crop and livestock production increases rapidly driven by population increase and dietary changes. This is also the case in baseline scenarios shown in Figure below that are based on FAO projections, and on MAGNET and IMPACT calculations ([[Stehfest et al. 2013]]). As a consequence of production increases, the total area of cropland and pasture is projected to increase, although this is less certain. Depending on scenario and region, some baseline scenarios may also show decreasing land areas, certainly after 2030 when the population starts to decline in several regions. | |||

|Example=Numerous policy interventions can be studied with the linked IMAGE-MAGNET and IMAGE-IMPACT framework: | |||

* Biofuel policies: Partly as an autonomous process under high oil prices but mainly driven by biofuel policies, the proportion of biofuels (so far, only first generation) in the transport sector is projected to increase ([[Banse et al., 2008]]). The model can be used to estimate direct and indirect land-use change and associated emissions. | |||

* REDD policies: Forest protection leads to a reduction in CO2 emissions from land-use change. The related opportunity costs can be used to estimate cost curves for the emission abatement that results from REDD policies ([[Overmars et al., accepted]]). | |||

* Agricultural and trade policies can be assessed for their effects on land use, greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity ([[Verburg et al., 2009]]). | |||

* Measures to reduce biodiversity loss by increasing protected areas, increasing agricultural productivity, dietary changes, and reducing waste ([[PBL, 2010]]). Several biodiversity options, in a stepwise introduction, affect land and commodity prices as well as land-use change (Figure below). | |||

* Consumption changes, dietary preferences, and their effect on global land use, prices and emissions can be studied ([[PBL, 2011]]; [[Stehfest et al., 2013]]) | |||

Changes in crop and livestock production systems, such as more efficient production methods, or organic farming can be assessed ([[PBL, 2011]]; [[Westhoek et al., In preparation]]). | |||

}} | }} | ||

Revision as of 15:19, 21 May 2014

Parts of Agricultural economy/Policy issues

| Component is implemented in: |

|

| Related IMAGE components |

| Projects/Applications |

| Key publications |

| References |